Ledger Art

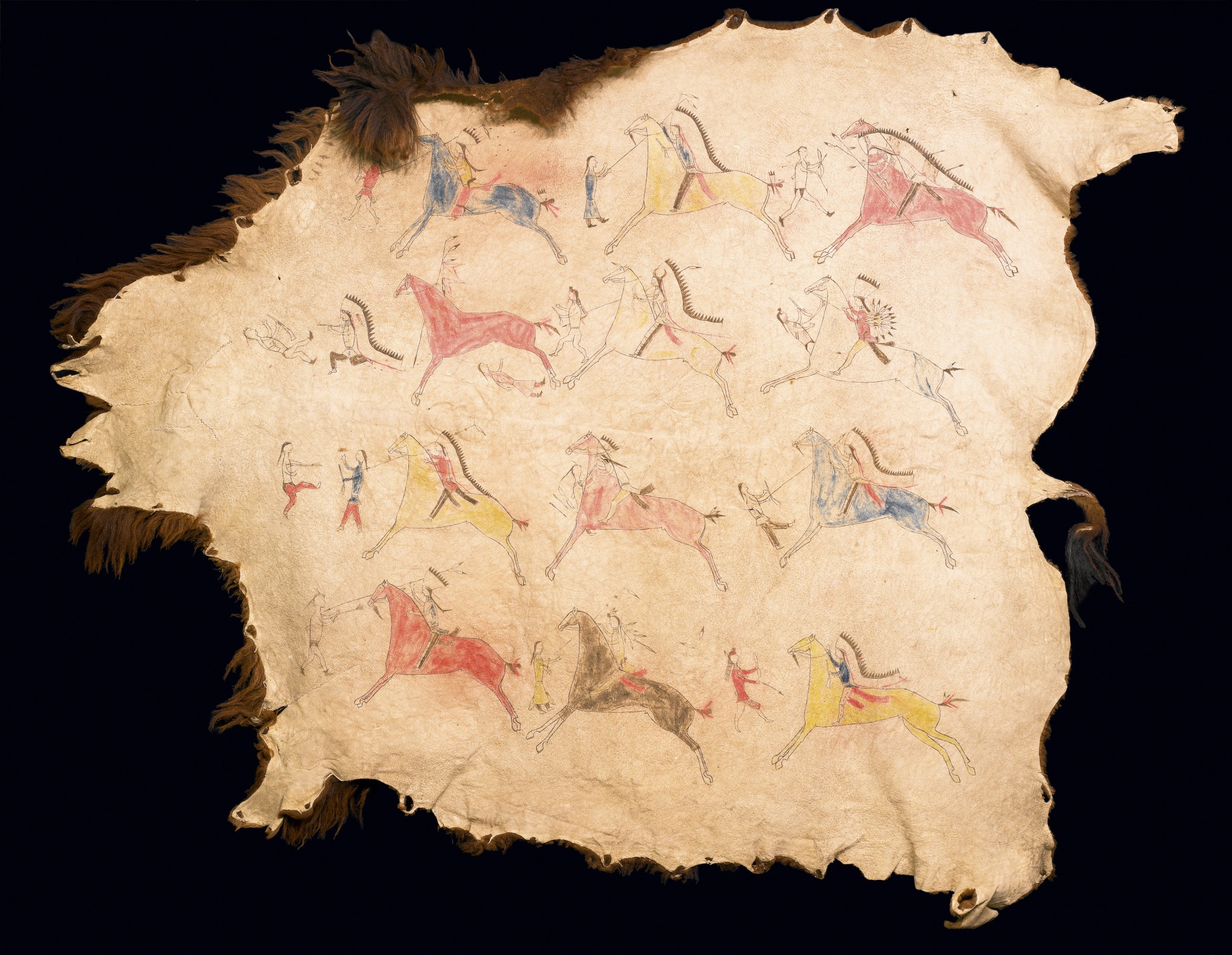

Historically, Plains warriors chronicled the heroic lives of great warriors and chiefs by depicting their experiences of war, hunting, religious ceremony, and courtship on rock, buffalo (American bison) hides, robes, and tipis.

Sioux, pictorial buffalo robe, about 1870. Buffalo (American bison) hide, paint, ink, and sinew, 86 × 102 3/8 in. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College: Purchased through the Florence and Lansing Porter Moore 1937 Fund; 2009.13.

From the early 1860s through the 1880s, Western expansion brought a steady stream of settlers, entrepreneurs, and soldiers to the Plains region. Plains warrior-artists acquired record-keeping books, called ledgers, as well as muslin, ink, pencils, colored pencils, notebooks, and sketchbooks from European Americans. The drawing style, or conventions, used for hide painting were carried over into these new drawing materials.

American (Southern Inunaina and/or Southern Tsistsistas), active late 19th century, Untitled (A Crazy Dog Society Warrior), page 172 from the Frank Henderson Ledger, about 1882. Graphite and colored pencil on laid ledger paper, 5 5/16 × 11 7/8 in. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College: Mark Lansburgh Ledger Drawing Collection; Partial gift of Mark Lansburgh, Class of 1949; and partial purchase through the Mrs. Harvey P. Hood W’18 Fund, and the Offices of the President and Provost of Dartmouth College; 2007.65.51.

Ledger drawings commonly feature a single figure in full regalia, displaying himself before an adversary. The physical setting is usually not represented because the scene was understood to be in the Plains. Scale, or the relative size of figures and objects, was also not as important as the story, which typically moved across the page from right to left.

Hunkpapa Lakota, tipi liner depicting Cehupa’s (Jaw) exploits, about 1910. Muslin, paint, porcupine quills, rawhide, native-tanned hide, cotton cloth, tin cones, dye, wool yarn, ink, string, and thread, 34 13/16 × 147 1/4 in. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College: Purchased through the Mrs. Harvey P. Hood W’18 Fund; 2009.10.

Ledger artists in the late nineteenth century drew both nostalgic scenes of pre-reservation life and images of the cultural changes they experienced. Later drawings continued to serve as personal narratives, but during the reservation era they also served as a form of resistance to Western expansion and cultural dominance by preserving Native American history and cultural identity.