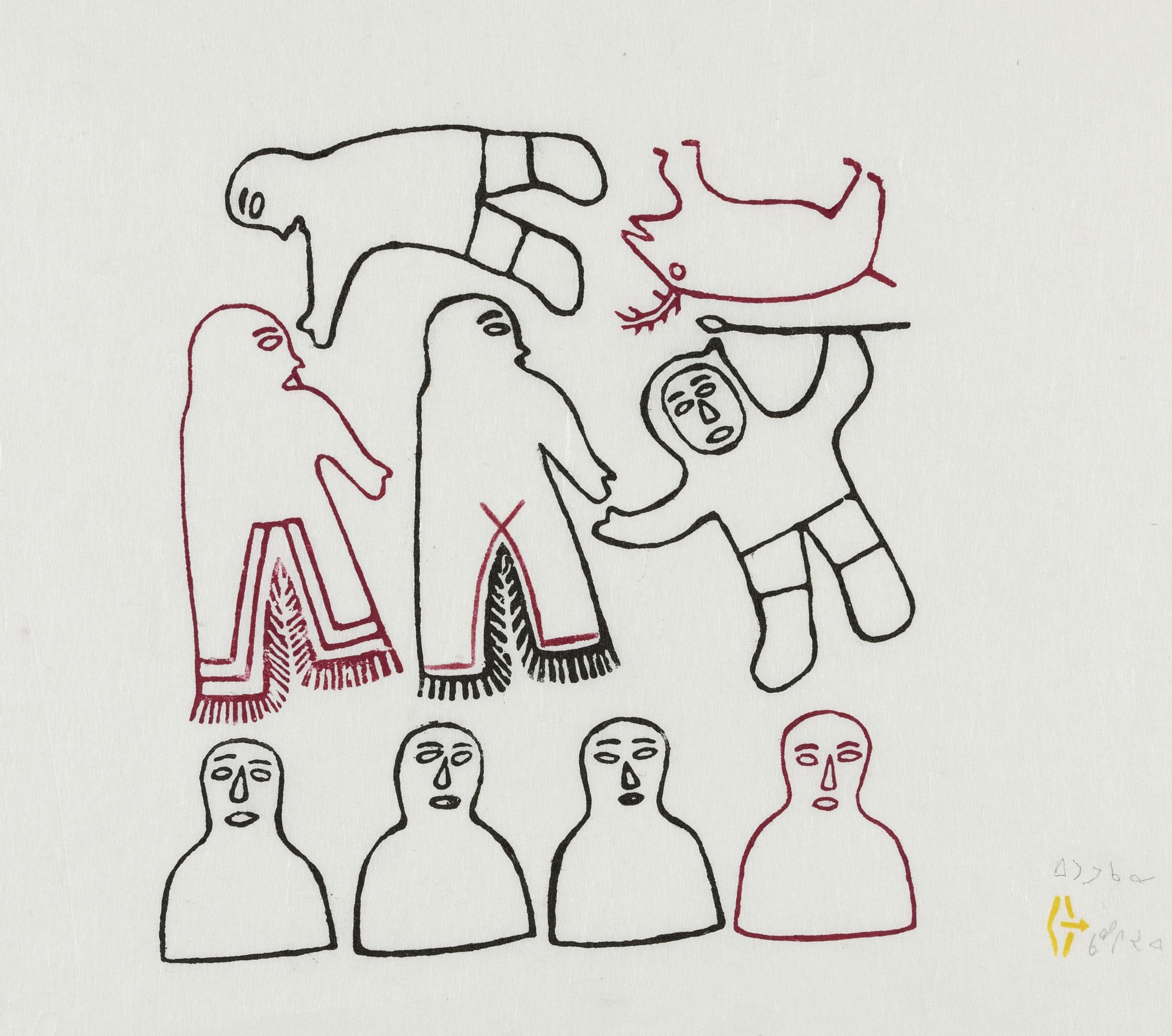

Seepee Ipellie, Canadian (Inuit), 1940–2000

Bird with Spread Wings

- 1983

- Polished gray serpentine

- 10 5/8 × 13 × 3 9/16 in.

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College: Gift of Jane and Raphael Bernstein; 2011.64.15

visibilityLook & DiscussThis sculpture by Seepee Ipellie (Ih-PELL-ee) embodies many of the qualities of modern Inuit carving, a new art form rooted in tradition.

explore the object

Prior to the 1930s, the Inuit were migratory. They travelled by kayak or dogsled to winter and summer camps, following the animals upon which their survival depended. They had no use for large, heavy sculpture, no permanent home in which to place them, and no time for carving and polishing large blocks of stone. They did, however, create carvings on tools, as well as small-scale sculpture in the form of amulets for protection and miniatures for children. These small sculptures would have been held in the hand or strung on a piece of string and worn.

After the 1930s, many Inuit moved into settlements and engaged in the larger cash economy of Canada. There, they used the skills honed over many years to create carvings for the art market. Over time these sculptures became increasingly large, highly polished, and stood securely enough to be exhibited on a pedestal. These carvings, created primarily by men who were also accomplished hunters, show a keen understanding of the animals they depict. They embody many aspects of traditional life and values.

The shape and color of this bird suggests that it is a raven. The raven does not migrate south, but remains in the Arctic all year long. According to Inuit creation stories, the raven made the world and the waters with the beat of its wings. It possessed the powers of both a bird and a man, and could transform itself back and forth at will. The majestic pose of this bird seems to reflect all of these qualities. It is powerful and enduring and as such seems to stand as a symbol of cultural pride and identity.

meet the artist

Seepee Ipellie began carving during a stay in a tuberculosis hospital when he was only fifteen. Like many Inuit infected with this deadly disease in the 1950s, he was taken by a Canadian medical ship to a hospital hundreds of miles away from his community. Inuit patients, unable to speak English and often isolated and afraid, received small pieces of carving stone or drawing materials to occupy their time. Some, like Seepee Ipellie, transformed these harrowing experiences into a livelihood when they returned to their communities.

learn more

Inuit scholar shares information about this sculpture and the artist Seepee Ipellie.