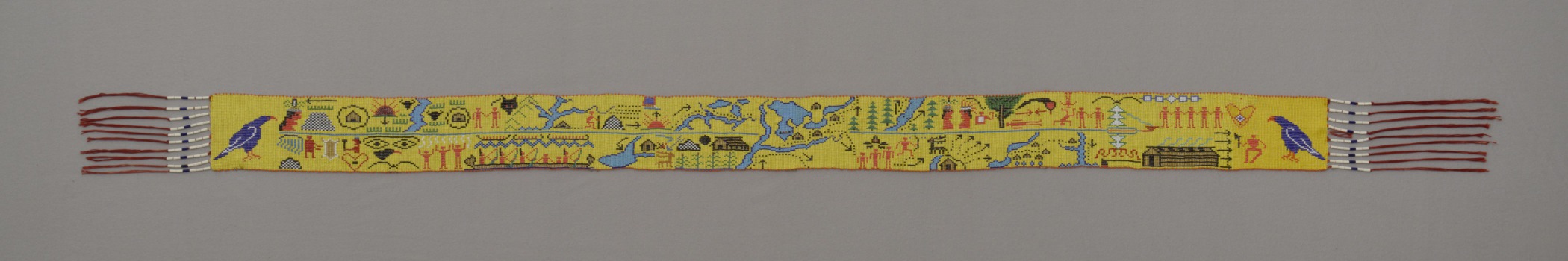

Ray Tehanetorens Fadden, American (Mohawk [Haudenosaunee (Iroquois)]),

1910–2008

Beaded belt depicting the story of the Iroquois migration

- 1958

- Glass beads, thread, and dye

- 64 15/16 × 4 1/4 in.

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College: Gift of Richard Brisson; 985.35.26453

visibilityLook & DiscussPictographs—pictures representing words, phrases, or entire events—were the earliest form of writing for cultures all over the world. The people of the Northeast Woodlands once carved pictographs into stone, incised them into pottery, or wove them into beaded belts to tell stories. The designs served as a mnemonic device to help aid the memory of the storyteller.

Originally beaded belts would have been made of wampum, purple and white beads made from whelk or clam shells.

Later, Woodlands people acquired glass beads through trade with Europeans. These beads allowed the maker to create belts of many colors. These record belts varied from 2 to 6 feet long and helped preserve the cultural history and stories of a people.

The story told in this belt is about the early migrations of the Haudenosaunee people. The maker of this belt, Ray Fadden, heard the story from an elder of the Tuscarora Turtle Clan who was born in the 1800s. Fadden created this beaded belt to record and share the story. He also helped to produce a pamphlet explaining the images. The narrative found below comes from that pamphlet (“Migration of the Iroquois” by Aren Akweks, Akwesasne Mohawk Counselor Organization).

Look & Discuss

Find each detail below in the belt as you follow along with the story. To begin, find the light blue line running through the belt’s center. The story moves from left to right above the line, then goes back to the far left and continues below the line, ending in the images on the far right.

The story begins:

This story is about the Ongwe-Oweh (Iroquois).

Many (a heap) winters

in the past (an arrow going backwards)

the Ongwe-Oweh lived toward the setting sun (west).

They lived where the grass grew tall and where the buffalo lived (Great Plains.) They lived beside the Great River (the Mississippi).

They dwelt near the villages of the Wolf Nation (Pawnee Indians). They were friends and allies of the Wolf Nation.

Northeast of their country were the Great Lakes. To the west rose the Rocky Mountains. Near the outlet of the Big River, the Mississippi, were the villages of the Iroquois.

For some reason, the Iroquois packed their belongings on their backs and migrated.

The narrative goes on to describe the many conflicts and adventures the Iroquois had along the way until they arrived in the Northeast Woodlands.

Eventually, they formed alliances with other tribes in that area. Each nation had its own identity and included the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca.

The end of the belt depicts this story:

The Five Nations became as brothers.

They were known as Kanonsiionni, the Long House of one family. Their government was called Kayenerenhkowa, the Great Peace Law. They worked together, and if any of these nations was attacked, the injury was felt by all of the Five Nations.

Under the tree of Peace were buried all weapons of war, and the Eagle, guardian bird of the Iroquois, rested on top of the Great Tree.

Meet the Artist

Ray Fadden created this belt in the 1950s. Although Fadden is non-native, his wife, Christine, is Mohawk. Fadden spent much of his life learning about and helping to preserve Haudenosaunee culture and history. He and his family founded the Six Nations Museum in Onchiota, New York, a museum devoted to teaching about Haudenosaunee culture. The tribe granted him membership status and fought for him to receive the full rights and privileges of a Haudenosaunee tribal member before he died.

Learn more

The National Museum of the American Indian’s Haudenosaunee Guide for Educators is an excellent introduction to the history and culture of the Haudenosaunee people.

Visit the website of the Six Nations Museum founded by Ray Fadden and his family.