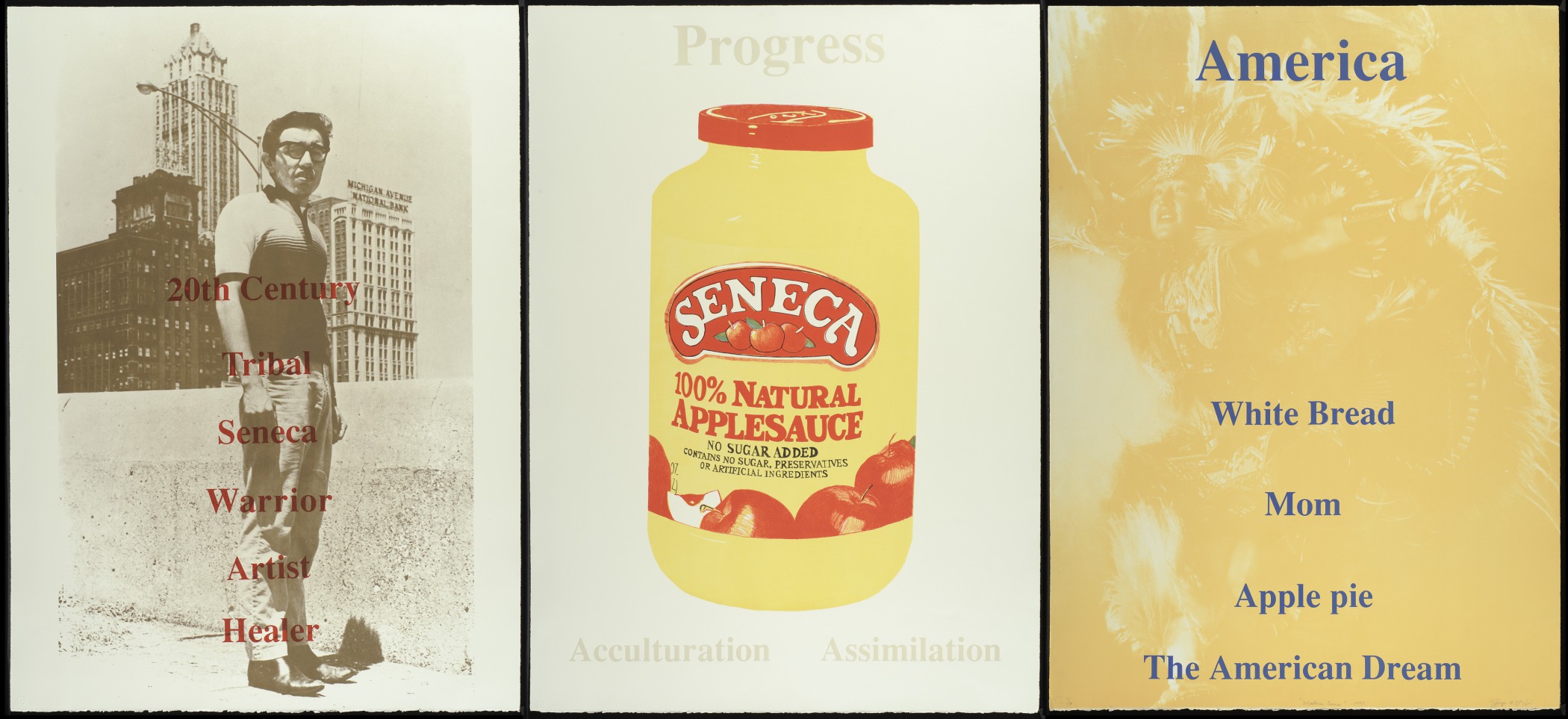

Rebecca Belmore, Canadian (Anishinaabe [Chippewa/Ojibwa]), born 1960

Fringe

- 2007

- Digital print on archival paper

- Image: 21 × 63 in.; sheet: 26 × 67 7/8 in.

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College: Purchased through the Elizabeth and David Lowenstein and the Olivia H. Parker and John O. Parker ’58 Acquisitions Fund; 2010.65

visibilityLook & DiscussContemporary Anishinaabe artist Rebecca Belmore created this work, in which she uses her own body to explore issues of history and identity.

Explore the object

Rebecca Belmore said of this work, “Some people look at this reclining figure and think that it is a cadaver, but I look at it and I don’t see that. I see it as a wound that is on the mend. It wasn’t self-inflicted, but nonetheless, it is bearable. She can sustain it. So it is a very simple scenario. She will get up and go on, but she will carry that mark with her.” 1

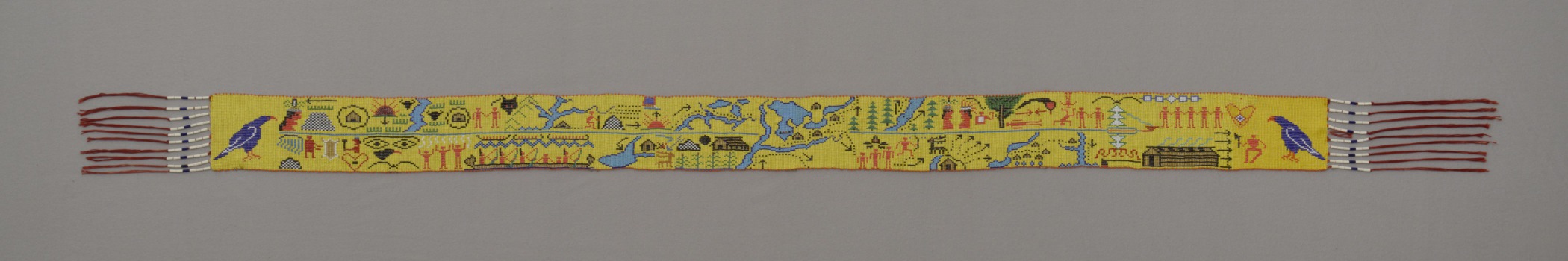

In this work, Belmore documents a kind of performance art. She staged the photograph to show herself as a woman who has been wounded and treated. Her wound could only have been attended to by others, given its position on her back. It has not only been stitched, but also embellished with a fringe of beads.

Compare this work to a bandolier bag. Anishinaabe women have embellished clothing, ceremonial items, and regalia with beautiful beadwork for centuries. Producing and selling beaded objects helped Anishinaabe women support their families economically after the arrival of Europeans.

What do you think Rebecca Belmore is saying about the power of community and native culture to heal the wounds of history?

Note 1. Rebecca Belmore in conversation with Kathleen Ritter, Vancouver, April 19, 2008, as quoted in “The Reclining Figure and Other Provocations,” in Rebecca Belmore: Rising to the Occasion (Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 2008); reproduced with the permission of the author.

meet the artist

Rebecca Belmore was born in Upsala, Ontario, Canada. She spent her summers visiting with and learning from her grandparents in Northwestern Ontario. As a teenager, in keeping with a Canadian practice that encouraged assimiliation, she was sent to high school far away and lived with a non-Native family. Much of her work deals with issues of cultural loss and dislocation, stereotypes of First Nations people, and social justice. Her performance-based work combines photography, sculpture, installation and video. In 2005, she was the first indigenous woman to represent Canada in the Venice Biennale, a bi-annual event considered one of the most important exhibitions of contemporary art in the world, and is a recipient of the Canadian Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts.