Chief Killer (Noh-hu-nah-wih), Southern Tsistsistas, 1849–1922

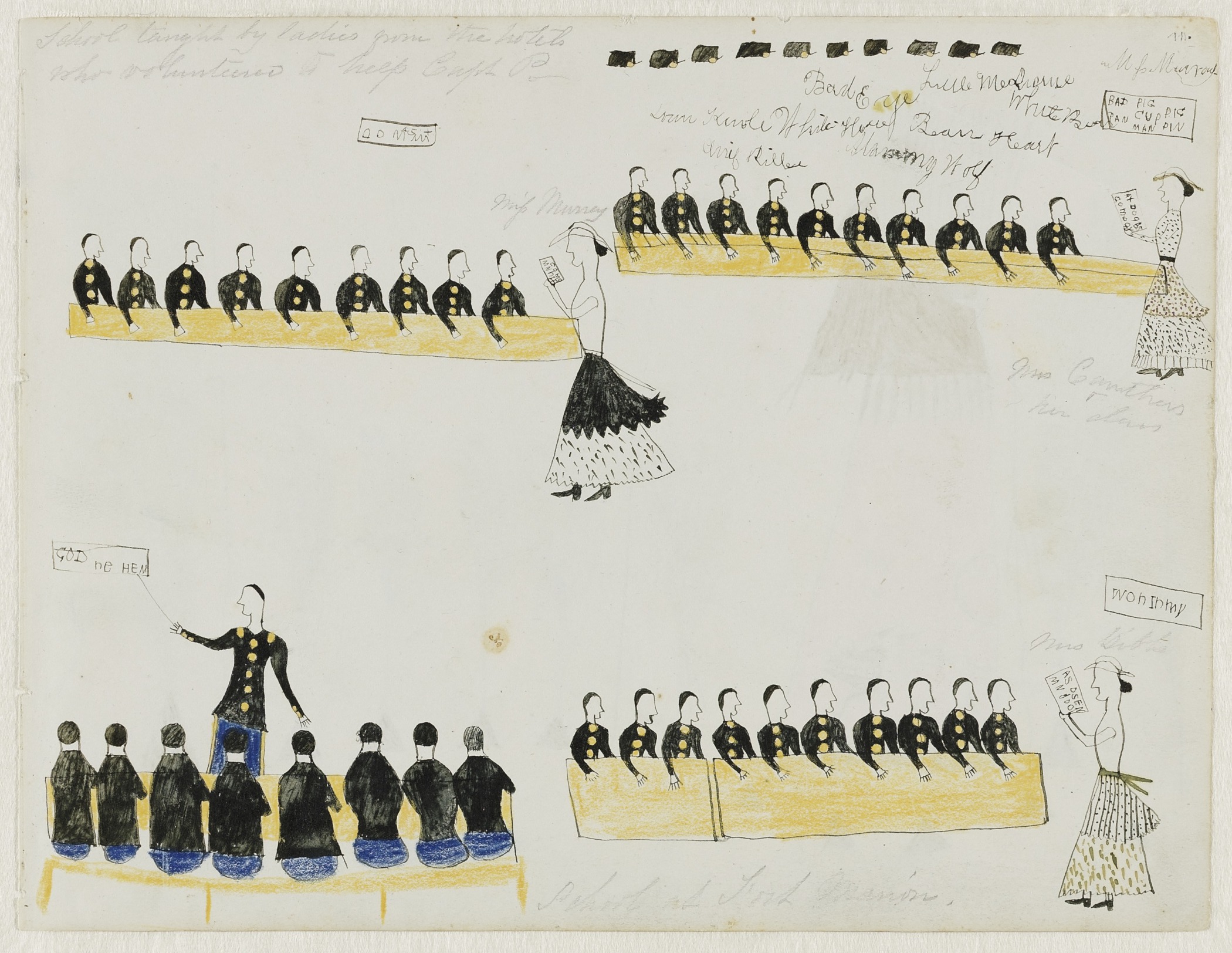

Untitled (“School taught by ladies from the hotels who volunteered to help Capt. P.”), page 11 from a Chief Killer sketchbook

- About mid-1875–mid-1878

- Pen, ink, colored crayon, and graphite on wove sketchbook paper

- 8 5/8 × 11 1/4 in.

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College: Mark Lansburgh Ledger Drawing Collection; Purchased through the Robert J. Strasenburgh II 1942 Fund; D.2003.18.1

visibilityLook & DiscussWhen the Southern Plains Indian Wars ended in 1875, US troops captured 72 of the most influential Ka’igwu (Kiowa), Tsistsistas (Cheyenne), Inunaina (Arapaho), Caddo, and Niuam (Comanche) chiefs and warriors, accused them of suspected crimes against settlers and soldiers, and imprisoned them at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida, until 1878. Their imprisonment was intended to ensure the peaceful conduct of their tribes onto reservations.

Unexpectedly, it also resulted in a new Native American art form. Historically, men on the Plains had drawn images of the heroic deeds of great warriors and chiefs onto rock, buffalo hides, robes, and tipis. Recognizing their ability to draw, Captain Richard C. Pratt, the officer in charge of Fort Marion, provided his captives with pencils, crayons, pens, watercolors, ledger (record-keeping) books, autograph booklets, and sketchbooks, and encouraged them to draw their memories and recent experiences. These works are known as ledger drawings or Plains graphic arts.

Chief Killer, a Southern Tsistsistas/Suhtai (Cheyenne) warrior imprisoned at St. Marion, made this drawing.

explore the Object

Captain Pratt believed that in order for Native Americans to achieve acceptance and full citizenship in the United States, they needed to give up their culture, a process known as assimilation. He demanded that his prisoners give up their language and traditional clothing. He required that they convert to Christianity and learn a Western trade.

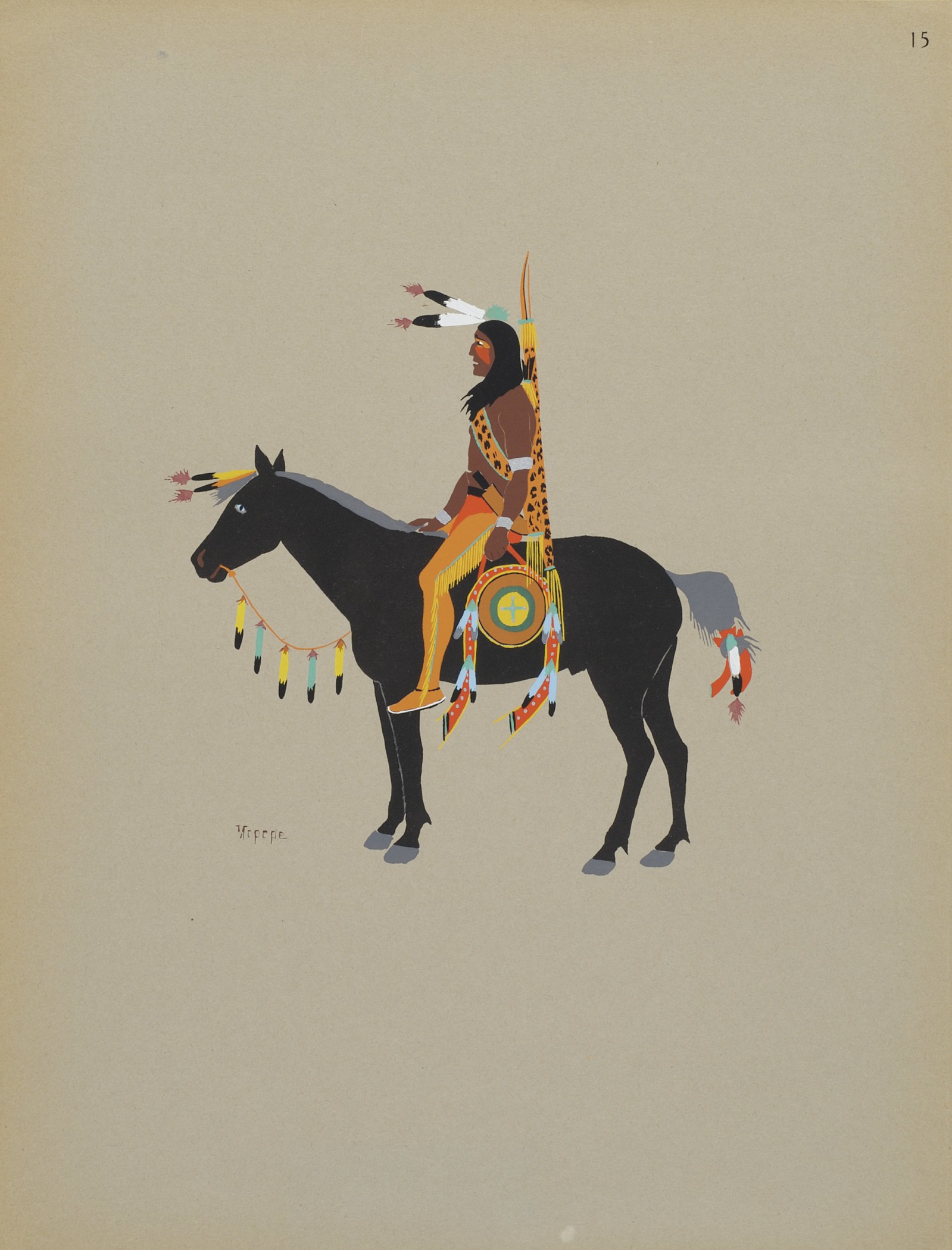

In the past, community members would recognize warriors drawn on buffalo hides by their clothing, shields, and horses. Absent any indicator of individual identity, an outsider wrote the names of many of the warriors on the back wall, including Howling Wolf, some of whose drawings are in the museum’s collection.

Pratt encouraged St. Augustine townspeople and vacationing tourists to the area to support the captives’ new artistic practice by purchasing their drawings as souvenirs. This commercialization of ledger art immersed the prisoners in the capitalist economy. Through their intensive interaction with their American patrons, the Fort Marion artists developed a drawing style that was unlike reservation ledger art. Ultimately, they merged Western traditions with Plains artistic conventions and created a powerful new art form. These drawings serve as important primary documents of this painful period in Plains history.

Learn More

In this video, Dartmouth Professor of History and Native American Studies Colin Calloway discusses this drawing and the history of ledger drawing.

Search the Plains region of the Hood Museum of Art’s collection database to see other examples of ledger art.